Imagine the stereotypical organic grower working in their garden during the summer: dungarees tucked into wellies, straw hat perched jauntily atop sunkissed hair, and a light trowel in hand. Perhaps a small glass of something pale and fizzy sitting on the potting table for the wasps to investigate.

Now, contrast this lovely image with me, wearing a rubber full-face gas mask, a double layer of thick rubber gloves taped to my wrists, and a nylon apron better suited to a slaughterhouse than a polytunnel. More Walter White than Capability Brown, this, dear reader, is the outfit necessary to tackle this subject.

Fermenting away happily in a 220-litre barrel sits a mixture of such potency that it dissolves Instagram perfection. A quick sniff provokes a gag reflex. What is this evil brew, you ask? None other than comfrey tea.

Comfrey Tea

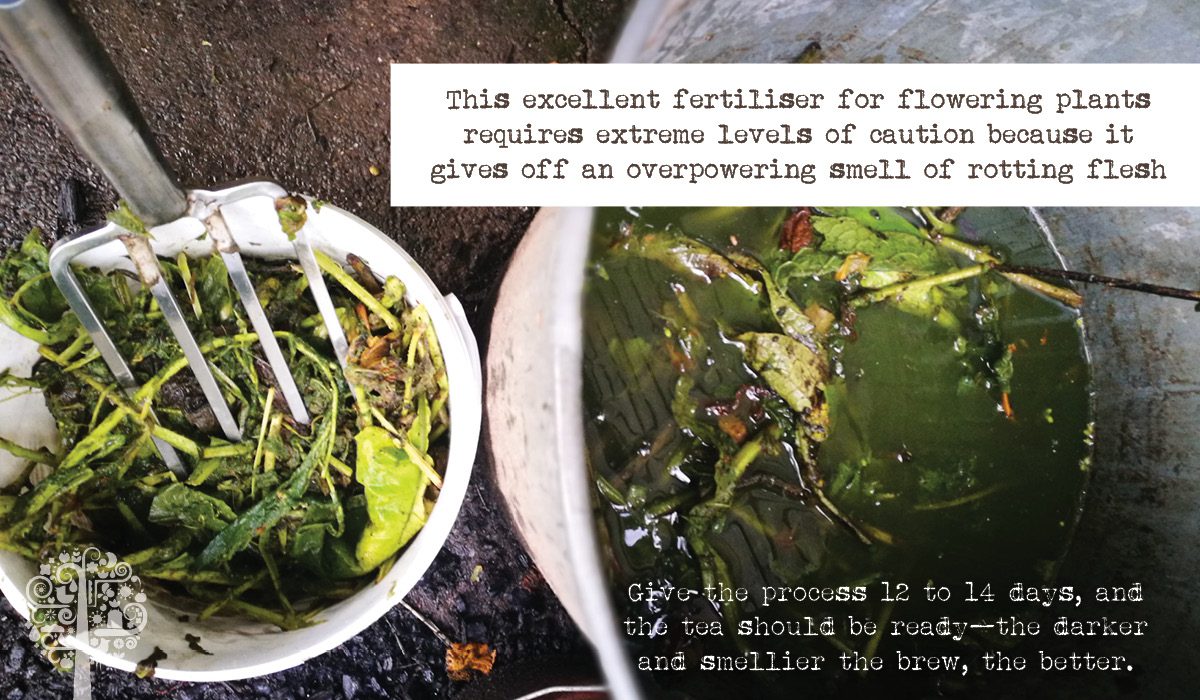

This excellent fertiliser for flowering plants requires extreme levels of caution because it gives off an overpowering smell of rotting flesh. Worse yet, (potential comfrey homebrewers, be warned) do not let it touch your skin, as the scent lingers for days, no matter what brand of fancy soap, essential oils, or bleach you use.

The retch-inducing honk of the tea aside, there are many reasons why comfrey is one of my top five favourite garden plants. It’s pretty easy to grow in abundance, hardly ever suffers from pests or diseases, and its nutritional content is the real deal for all flowering plants.

Medicinal Benefits

Before it became a simple garden plant for bumper crops, the medicinal and healing properties of comfrey were valued for hundreds of years. Its Latin name ‘Symphytum’ comes from a marriage of words’ Sympho’ – ‘grow together’ and ‘Python’ – ‘plant’. The old common name for it was Knit bones, thanks to its reputed property of healing broken bones quickly. This practice has been abandoned since the development of modern medicine, especially considering that if the bones weren’t properly set before applying comfrey poultice, they would heal unevenly, which then required breaking and resetting. Just the thought of that scenario makes my legs hurt!

The magical compounds responsible for easing arthritis pain, inflamed joints, cuts, wounds, sprains and bruises are pyrrolizidine alkaloids, which comfrey has in abundance. Notably, one called allantoin speeds up the cell-healing process and decreases inflammation. Back in the day, comfrey root was also used for the treatment of mouth ulcers, soothing irritation of the digestive tract, and easing chest infections thanks to its mucilaginous properties.

There are two sides to this medal of honour, unfortunately. The oral application of comfrey root was abandoned after several cases of liver damage in patients, and it was later discovered pyrrolizidine alkaloids are toxic, particularly echimidine. Echimidine is present in Russian comfrey (Symphytum uplandicum), which is the most popular hybrid of comfrey nowadays. Oral use of Symphytum is now limited to drinking weak tea for less than six weeks to help bone healing; however, the most common and safe medicinal use is to make a poultice.

You can do it from the root only if you apply directly to the skin. Or, mix the root with mashed leaf and ‘sandwich’ the mixture between gauze, as the leaf has small hairs which can irritate the skin if applied directly. In modern-day skincare, allantoin is widely found in sun care lotions, anti-acne creams, and products promoting healthy skin. Creams containing the compound are never as potent as the leaf itself.

What It Looks Like

Comfrey has a broad, hairy leaf with a deep green colour and is adored by bees, especially bumblebees. Flowers range from hues of deep purple and pink to cream-yellow and white. The colour depends on the variety of comfrey growing. However, they hybridise easily between species, and it’s often challenging to tell which one is growing. Symphytum prefers damp and semi-shade areas to grow; it’s usually found in ditches and wetlands.

Nutritional Profile

Fellow plants highly regard comfrey for its excellent source of nutrition. It’s rich in all three macronutrients as well as micronutrients such as calcium and silica. The NPK values of a dried comfrey leaf are estimated at around 1.8–0.5–5.3 when the plant is in flower, but when it’s in the vegetative state, it has higher nitrogen, making it an ideal food for seedlings.

Making The Brew

Gardeners want to watch for the first flower sets, usually early in spring as the plant sprouts from the ground. Grab a bucket, a long stick for stirring, and a pair of rubber gloves. Once the comfrey has emerged a bushy plant, chop half of its volume at about 5cm (2″) above the ground. The half you leave on the plant will mature and flower, giving nectar to the bees, while the cut part will produce new leaves. If you have more than one plant, chop one and leave one; you’ll have a constant supply of leaves for the brew and keep your pollinators happy.

Fill the bucket or water reservoir with the comfrey leaves, stems and flowers. If planning to use a butt with a tap on, use only leaves, as the stems are slower to break down and their fibres are likely to block the tap. This sounds like little to be worried about, but it’s all well and good until you have to submerge your whole arm in the anaerobic sludge to unblock it! Don’t try this before a romantic date.

You can also use an old potato sack as a giant tea bag, which allows the water to penetrate the contents and leave all the fibrous pulp inside. If you have an air-tight lid for your container, make sure you burp the top every few days, as the gas generated by the fermenting bacteria will inflate the bucket and likely cause a small explosion. I leave mine open, as it also keeps any nosey allotment visitors away from the plot – at least those with a working sense of smell. Give the process 12 to 14 days, and the tea should be ready—the darker and smellier the brew, the better.

Tea Time

Once the stinky potion is ready, mix it with water and feed it to your plants. There are many dilution ratios suggested for the finished brew, but a good rule of thumb is to make it the colour of a weak tea. If the undiluted brew is deep green, the ideal concoction may be as much as ten parts water to one part comfrey concentrate. A more diluted tea is recommended at the beginning of flowering, and a full blast once the fruit starts to set. It’s always better to dilute the tea with water, as the oxygen in the water will limit the numbers of parasitic and detrimental organisms present in the solution; after all, it’s still a living thing!

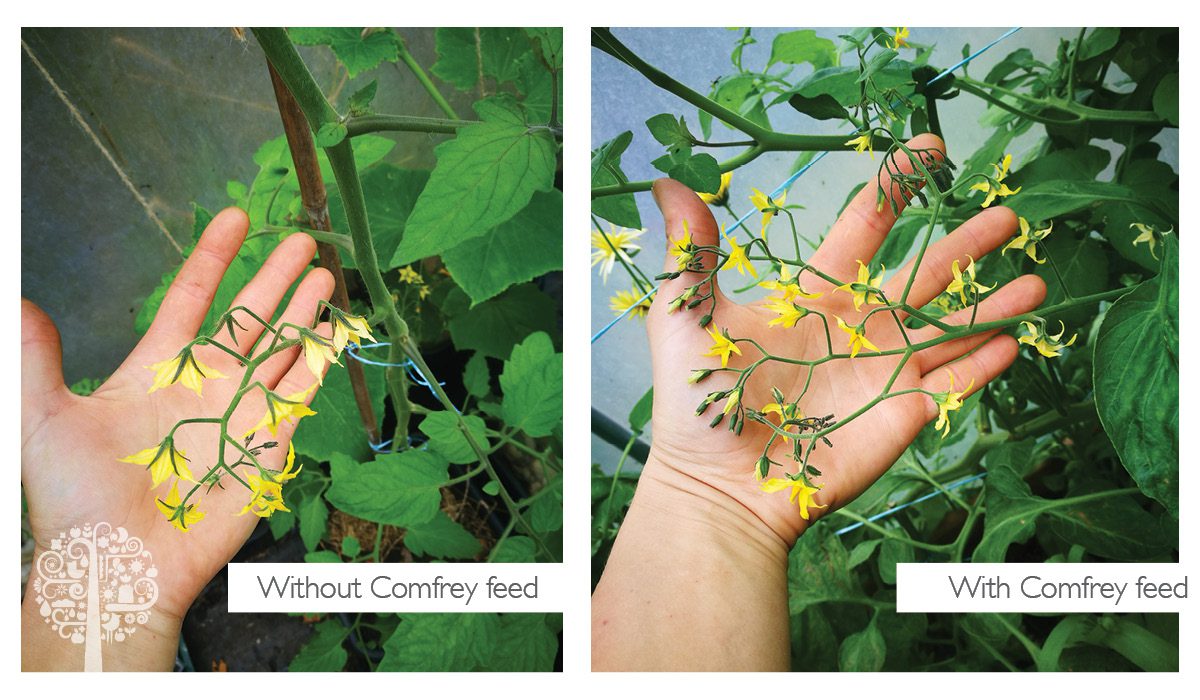

When your fruit, vegetables and flowers have entered the bloom stage, feed them once or even twice a week and the results will show very quickly. Flowers will be larger and more sets visible, trusses of tomatoes (depending on the variety) will double, triple, and even quadruple before your eyes. The much-needed potassium will be forcing your plants to give its best.

With zero-waste in mind, after the tea is finished, scoop out the soggy plant material from the bottom and use it as mulch on your vegetable patch. The organic waste will break down into the top layer, feeding not only the plants but also the soil biome.

Final Notes

It is worth remembering that the temperature also plays a role in this process. My timings work for the UK and similar climates, but if in sunny and hot parts of the globe, your brew may take as little as seven days to make. Similarly, if you’re in a colder neck of the woods, it will likely take longer.

Another note: my opening lines are no exaggeration. The smell of the massive barrel of comfrey tea in my polytunnel is so strong, I can barely breathe, even with the gas mask. Unfortunately, we only have one mask, so those around relying solely on holding their breath face an uphill battle. I highly recommend locking up the mask, making sure no one else knows the combination to the safe.

Wish I’d read this before decanting my first ever batch of comfrey tea – I did it bare handed. I still smell. On reflection, I probably shouldn’t have tried making it in an urban area either. Sorry neighbours.