Food Forest in the Laurentian Mountains: Wild Orchard Gardens

The main work of a food forest is meant to be harvesting. That’s a pretty good sell for anyone who has tried to grow food successfully. There are so many models, most anciently the Garden of Eden, though you might avoid that apple variety.

I grew up in a small suburban garden in Southern California surrounded by fruit trees, a small pond and vegetable garden, a hen house, and rabbits. I planted the second forest garden in Georgia in an old pecan grove. By then, I could integrate permaculture practices into a garden. The third was an urban version in Montreal between buildings, and the fourth was in a UK allotment. Each of these varied settings supported a garden that embodied at least some of the design principles of a food forest.

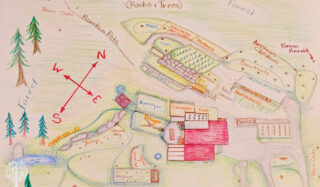

Finally, in my sixth decade, I have landed on the south-facing hillside of an actual forest. And because we are on the Canadian shield, we have rocks. Often seen as a thorn in the side of garden cultivation, many of these are so large that they stack nicely into walls that support terracing. They collect and radiate heat into whatever grows before them, creating micro-climates throughout the garden. This terraced forest garden also integrates the principles of a food forest.

An Edible Forest Garden Mimics Nature

It was interesting to plant a forest garden surrounded by an actual forest. Even in our poor, rocky soil, the mycelium network insinuates itself into plantings, enriching what the plants have to work with. The nut trees are interplanted with existing maple and beech. They benefit immediately from this, as long as one has dealt with the light issues.

I planted nut trees as a substitute for grains. Like all trees, they bring up nutrients from deep within the soil. However, the nutrition carried in nuts is different from that of commercially grown grains, and they store well for a few years. Fruit trees and berry bushes also gather nutrients widely and hand them over in fruit that can be processed for the winter. And the great blessing is that none of this ever has to be replanted. Once they are established, it’s down to the mulching, pruning, and harvesting.

What’s For Dinner?

My garden features a collection of 50 walnut, hazelnut, and chestnut trees, 35 apple, pear, plum, peach and cherry trees, five kinds of berries and two grape varieties. I have also snaked in a collection of perennials to balance winter diets. Add asparagus, Jerusalem artichokes, perennial chard, perennial herbs, and an array of wild native plants; throw a root crop harvest into the mix from the growing season, and one has a passable, pretty balanced winter diet. It’s not food entertainment, but it’s undoubtedly eating well.

Design Considerations for Your Food Forest

Forest gardens are mainly about design, planting, and then waiting for the trees and shrubs to mature and begin to yield groceries. Here is a checklist of considerations to make as you embark.

- What do you want from your forest garden? Food, health, beauty, increasing biodiversity, comfort, community?

- What scale are you working with? What are the mature sizes of the trees and plants you want to use?

- What is the sun’s position in your space(s) throughout the day? This is critical. We had to take down some of the large dense evergreens to the south and west of the property to give the garden enough light for food production. Food doth not grow in the shade.

- What are your constraints? Buildings are usually non-negotiable, but driveways, for instance, could be removed.

- Plant forward from your edges. Moving from the north toward the south, plant highest to lowest so that as the trees mature, they are not blocking the sun for the lower canopy. This is where pruning and transplanting are essential as the garden changes and grows.

- Develop plant guilds and annual crops between early plantings. A typical mistake is overplanting a site. While waiting for your trees to grow, you can always plant annual crops and add plants like comfrey and cover crops to build soil.

- Integrate food for wildlife. Plant things to feed your woodland neighbors and keep them out of your more precious crops. For instance, when we took down the evergreens, we planted burr oaks on the garden’s outskirts and white clover in the open areas. This created food for nut eaters and grazers.

- Build your soil! While you wait for your trees to mature, spend time improving the health of your soil. Find ways to amend it by developing composting practices, adding animal bedding, chipping prunings, etc., so you always have something to mulch with.

Strategies for Having Food Everywhere

As I mentioned, one of the design principles is to plant down from an “edge” toward the south (or even west). For instance, planting forward from the outside edge of a forest in descending plant sizes. What are your borders, and how can you best move forward from them? South-facing walls and fences present excellent edges. However, a west-facing wall could be a wonderful home for a grapevine, and growing vertically integrates a large vining plant in an otherwise unused space.

Benefits of Using the Edible Forest Garden Model

- Localising food systems

- Maximizing food yield by employing intensive growing practices

- Building resilience through increasing biodiversity

- Building self-supporting systems

- Enjoying the intrinsic value of reciprocal relationships with nature.

Whether your food forest is a collection of plants surrounding a single tree or a more full-blown version, take time to plan it, but don’t hesitate to make it happen.

Marci’s recommendation for further reading: Edible Forest Gardens, by Dave Jacke, volumes one and two.

Trending Articles Today

Similar Articles

Boosting Food Sovereignty And Community Growth With Food Forests

It’s small-scale food production following permaculture practices and can be done almost anywhere. Jennifer Cole explains the many benefits of food forests.

Atlanta Home To Largest Food Forest In The U.S.

Some initiatives deserve to be applauded, and Atlanta’s giant food forest is one of them. The seven-acre plot is the largest such space in all

Fungi – The Key To A Successful Food Forest

A food forest is a permanent agricultural system that layers edible plants together. The secret to success is making sure fungal populations are thriving!