Passive Solar Geothermal Greenhouse at the 45th Parallel

Last August, we were screwing down the 14’x3′ sheets of double-ply PVC to the metal frame of the 60-foot greenhouse we were building on the mountainside. It was pouring rain. Once we’d finished screwing down the last sheet, we stood dripping inside the cocooned greenhouse listening to the pounding clatter. Standing on the sunken floor below the new roof, we felt we might finish building it before the snow came.

Extending The Growing Season

We had decided, for better or worse, to build a Greenhouse in the Snow Canada greenhouse last summer. Russ Finch, a retired-postal-worker-turned-market-gardener, engineered it for growing citrus in Nebraska. We were interested in a nine-month growing season. I had written to Russ a few years hence, asking if they shipped to Canada. It seemed complicated. But some folks in BC bought a franchise, and buying it became easier.

Breaking Ground

The construction began in late April 2022. Our neighbor Eric and his Kubota began to dig an 8’x4’x60′ long trench on the upper terrace of our hillside, just south of the butternut orchard. Because our orchards are planted on the mountainous terraces of the Canadian Shield, we were immediately treated to some huge rocks that the Kubota could barely strain from the earth. We had been encouraged to do an engineering site assessment by our friends in BC. Naively, I imagined it to be a technicality. It couldn’t have possibly articulated the boulder count. Over the following weeks, Eric continued digging a circular trench that was 10 feet deep and 250 feet long for the geothermal tubes. Ultimately, he had extracted enough large rocks to build the two terraces that secure the greenhouse to the mountainside.

After digging the greenhouse footprint and the trench, they began to fill with water. The words “engineering assessment” rang in my ears. However, it occurred to us that we might be able to drain the greenhouse into some wells at the west end.

We dug these as deeply as possible. The two well cylinders sit on a large rock sheet that runs the entire terrace’s width. This geologic wonder means that much of the water from the mountainside passes through the wells (and sometimes into the overflow). They have enabled us to water from inside the greenhouse the entire growing season.

At this point, there was still a lot of work to do, including:

- Digging and placing the footings;

- Building retaining walls for the front and back inside beds;

- Installing the metal super-structure, the north-facing insulated metal wall, and the south-facing PVC;

- Creating the back and front rock and soil berms;

- Building the east and west ends;

- Filling the beds with compost;

- Installing the blower for the geothermal system.

Planting

By September, I’d planted 100 experimental tomato plants on the greenhouse floor. With the two ends open, it was a brute of a hoop house with no airflow concerns. The tomatoes grew like savages. I transplanted some artichokes to overwinter and began seeding greens. A ginger plant that had lived in a pot for 12 years was planted inside. A friend asked me to overwinter her fig trees.

Hot House

Once the ends were built in late September, we began to experience the intense heat-up when the sun shone. The thermometers would bounce to 50°C unless we left the door and windows at the ends open. The tomatoes stressed, and the ginger jumped. But, by mid-October, the sun had fallen so low along the horizon that it was only hitting the back bed directly. The nights were cold, and I still had not assembled and installed the blower. These conditions did not make a happy tomato! They packed it in by mid-November, and the green tomatoes came down to the house for ripening.

Low-Tech, High Yield

The plan was to keep the winter growing as low-tech as possible: no heating or grow lights. The ginger, figs and artichokes would have to tough it out. And they did, though the figs were less than impressed.

The idea of passive geothermal is that the air temperature ten feet down maintains a steady state of 15°C. Blowing that air through the tubes should bring up the temperature in the greenhouse when it is -20°C or -30°C outside. They suggested that the slower air movement through the tubes would heat it better, but the airflow was undetectable with the blower on the lower setting. The plan remains to rewire it to medium this winter.

An Early Start

This year, I got started in the greenhouse in March. Deep snow was all around. Despite the overcast spring, cabbage, peas, and kohlrabi seeds sprouted by the beginning of April. The greens that had muscled through the winter were properly thinned. Once the cabbages were up, I felt invincible, so I went on and planted my flowers, including marigolds, sunflowers and calendula. Everything could be planted directly into the beds, then transplanted into pots to establish individual root systems and harden off.

By mid-April, the Mediterranean friends could be seeded: tomatoes, peppers, eggplant, and basil, with cucumbers and luffa representing the cucurbits and okra of the African subcontinent. As I moved the flowers, cabbage, and greens to pots, I moved the heat lovers into their summer homes. I had so much success with the tomato seeds-to-plants that I had a surplus to donate to the local elementary school. Next spring, I will prepare for a neighborhood plant sale.

My biggest first-year greenhouse growing takeaways were:

1. Seed germination times were not earlier in the season but took less time and grew faster.

2. The angle of the winter sun was the biggest impediment to winter growing.

3. Plant fewer plants. A single greenhouse plant will have three or four times the output of a plant living outside in similar conditions. For instance, I planted the cucumbers in regular spacing. I placed the little plants behind two 4-foot-tall slanted trellises. Within a month, they had topped the trellises and had begun to latch onto the training strings of the two nearby tomatoes. In mid-July, one of the groups of cucumber vines collapsed under its weight. The excessive vines had shaded its produce so that the fruit withered and the harvest was greatly reduced.

4. Interplanting is not a winner. Airflow must be respected. It would be cool to grow watermelon and cantaloupe on the floors of the beds (beneath the tomatoes and peppers) to maximize production. But soon, these vines were growing up and over everything, then mildewing, so they had to be added to the compost pile.

It Was Worth It All

Last summer, I spent considerable time wondering why I had dragged my family into such building shenanigans for a bit of veg. This summer, I can hardly imagine growing many things we like to eat without the greenhouse. It will be years before it is more than a happy experiment, but fingers crossed for lemons in 2024!

Trending Articles Today

Similar Articles

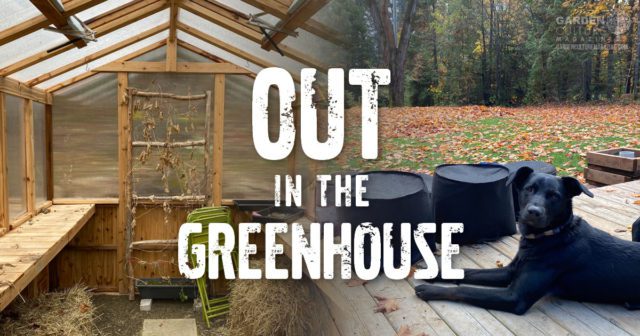

Out In The Greenhouse: What To Expect When Building Your Sanctuary

If you’ve been thinking about building a greenhouse in your backyard but still haven’t pulled the trigger, I have one piece of advice for you:

Out In The Greenhouse: Maintenance And Care

Greenhouse growers beware: there are many chores that need to be done every season to keep the greenhouse in tip-top shape. Here’s our fall maintenance guide.

Out In The Greenhouse: These Warm-Season Crops Will Thrive

The list of food crops and flowers that do well in a greenhouse is endless.

Lufa Farms Builds World’s Biggest Rooftop Greenhouse In Montreal

Montreal is now home to the world's largest rooftop greenhouse. Lufa Farms is growing food in the 163,800 sq ft space so that city-dwellers can eat fresh!