Pattern recognition is one of our most potent superpowers when it comes to survival. We know that those dents in the floor are animal tracks because we’ve seen the feet that made them. Millennia of observation taught us the patterns of the stars and seasons so we can use them for farming and navigation. A ball rolling out of a side street tells you to break because the child likely to come chasing after it. But this superpower also has a dark side; confirmation bias.

Confirmation bias is an interesting idea and one which can often cast light on a lot of things people do. If you’ve never heard of it (and don’t feel bad if you haven’t), it means how humans tend to see new information as confirmation of our existing beliefs or theories. In simple terms, we’re so great at seeing patterns, that sometimes we imagine one that’s not there.

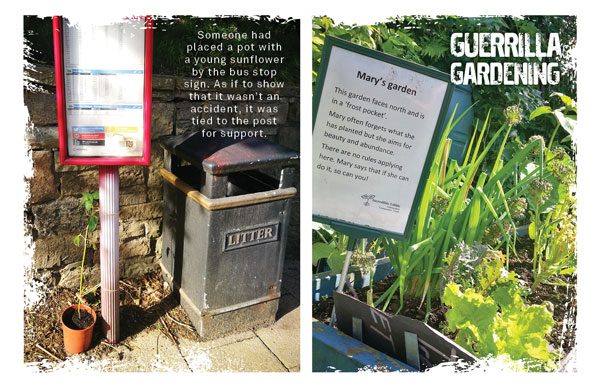

I might have caught myself using my confirmation bias this week. Walking by a bus stop near my house, I think I spotted evidence of a pattern of behavior I never used to notice but now see everywhere: guerrilla gardening. Someone had placed a pot with a young sunflower by the bus stop sign. As if to show that it wasn’t an accident, it was tied to the post for support. Perhaps it was part of a movement to add greenery to our increasingly unnatural environment.

Pollination Street

My first introduction to the quiet revolution that is guerilla gardening was meeting the originators of the Incredible Edible movement in Todmorden, a few miles from my home in West Yorkshire. Much has already been written about Mary Clear and her campaign, but this was my first taste of the impact associated with reclaiming barren public lawns and single-species verges for growing food.

Like all revolutionaries, Clear and her gang began small. Knowing that it is easier to ask forgiveness than permission, they sneaked food plants onto traffic circles and grassy roadsides. They made little community action signs telling passers-by to help themselves and maintained the plants until harvest.

When local council officials eventually noticed their actions, there was the inevitable power struggle, but they were already too popular to stop. Incredible Edible planting days, markets, and events have attracted thousands of participants and the attention of royalty! Prince Charles once told Clear that when he becomes king, she can plant wherever she likes. We’re all still curious to see if he keeps his promise should his head ever hold the crown.

The Incredible Edible movement has since blossomed around the world, with thousands of independent groups copying and expanding upon the initial idea and bringing locally grown produce and awareness of how to grow to millions of people. Todmorden still has its publicly-maintained growing spaces, such as on ‘Pollination Street’ in the center of town. And Clear has a good chunk of her garden open to anyone who wants to forage for rhubarb and cauliflower.

Capital Lettuce

One of London’s most impressive guerilla gardening projects is the so-called ‘magic roundabout’, which has been transformed from a dull traffic disc to a self-sustaining island of beauty, color, and joyful buzz of bees. We have Caroline Bousfield Gregory to thank for the makeover. Her pottery studio overlooks the roundabout, and she took it upon herself to improve the view. It’s now 18 years that she’s been chipping away at it, and the result is spectacular.

Bousfield Gregory grows and dries lavender flowers, turns them into scented cushions, and sells them to pay for more plants. She looks after the makeshift garden to this day. The thing that many people comment on when visiting her workshop is the ‘feel-good vibe’ the spot provides to the public. Sometimes, residents help Bousfield Gregory tend the plants, creating a sense of belonging in the community. She says many people work together with the council to plant in tree pits or create small wildflower meadows. This spreading of ideas and motivation is a theme common to all guerrilla gardening projects, and in my opinion, is the most critical result.

Why Break The Rules?

All of this isn’t without its risks, of course. In many places, planting without permission may be unlawful or leave the guerrilla gardener liable to being sued. Besides the legal consequences, there’s the danger of introducing invasive species and doing the ecosystem more harm than good. So why do so many still find themselves venturing out under cover of darkness with their trowels in hand to sneak plants into spaces where they “shouldn’t” be?

There seem to be three primary motivations:

Protest

From anger over the shortage of fresh produce in New York’s poorest neighborhoods to the daffodils my husband planted as a teenager in the shape of a giant phallus under his headteacher’s office window, there are as many messages as there are people to speak them. For many, the very absence of greenness in their world is worth protesting. Guerrilla gardening can be an effective action against landowners or authorities who allow public areas to decline into decay.

Community

Incredible Edible and many others demonstrate time and again the value of bringing people together to plant and to harvest. A truth as old as time, but it’s easy to lose sight of in the modern world of supermarket produce.

Joy

You’re reading Garden Culture Magazine. The chances are you understand this part better than I can explain it. The simple act of planting flowers can lift someone’s day, raise their self-esteem, and surround them with beauty.

My feeling is that most sneaky planting (including the bus stop sunflower) is motivated by a mixture of all three.

A Natural Urge

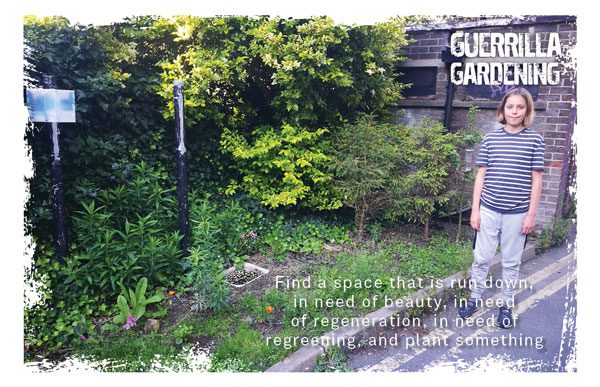

A couple of months ago, my friend, Sarah, put out a Facebook request for spare plants for her son’s planting project. While visiting the spot, I was impressed with what Jude has created. After just a few weeks of lockdown, he took a bare, forgotten patch by the town car park and introduced a variety of plant and tree species, a log pile, a small pond, and even a bird feeder. And best of all, this 12-year-old nature hero hadn’t ever heard about guerrilla gardening. Jude told me that he visited his friend’s garden with newts in the pond and an abundance of flowers, and felt he wanted to have a garden of his own creation. Living in a terraced house with no garden was not an obstacle; neither was a lack of resources, as he successfully gathered plants from people in town.

As we chatted about the species planted (foxgloves, violets, poached eggplants, and various other wildflowers), a blackbird was hopping in the car park looking a little irritated that we were so close to his new food and drink source. In the words of Ron Finley, whose guerrilla gardening TED talk went viral, “You’re changing the ecosystem when you’re putting in a garden”. The half-empty peanut tube in the bird feeder tells me that many visitors appreciate the space. Jude said that many people, mostly neighbors living across the patch, commented on the brilliant job he’s doing.

Primal Patterns

For me, Jude’s independent desire to make a green space of his own seems to point to a central truth about guerrilla gardening and about growing in general. We plant things because we want to be surrounded by the primordial pattern of the forests where our primate ancestors lived for millions of years. There’s an eternal tension between the built environment that we make for our comfort and the instinctive response we have to the beauty of nature. When the concrete jungle seems to be taking over, there is some part of us that won’t let it eat up every corner. That gives me hope for the future of our world.

Or, maybe that’s my own confirmation bias. Maybe someone tied the sunflower to the bus stop to come back for it later. There’s only one way to overcome this uncertainty: we have to keep making the pattern we want to see.

I urge you to go out and plant something. Find a space that is run down, in need of beauty, in need of regeneration, in need of regreening, and plant something. Do it safely, quietly, without fanfare. Do it as much as you can in as many places as possible. Change the pattern.