In recent years, we have seen an enormous surge in the amount of microbial-based products available to growers. These, undoubtedly, have added a third dimension to standard nutrient programs and increased the productivity of organic gardens.

When used correctly, these types of additives can provide massive benefits over a range of crops, such as increases in yield, speed of growth, plant resilience, and drought resistance. They can turn standard growing media and potting soils into thriving natural systems.

However, when overused, just like fertilizer, they can have a detrimental effect on soil and plant health.

There is a diverse range of fungal and bacterial inoculants available in many products, sometimes in isolation, but more often as blends. What do they do? And when is it appropriate to use them?

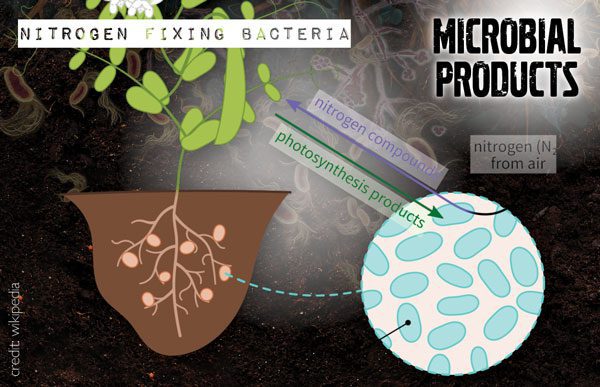

Nitrogen-Fixing Bacteria

These little guys take nitrogen from the air (N2) and fix it into the root system in the form of Ammonia, which is readily useable by plants. The main types available are the non-symbiotic types, such as Azotobacter, that live alongside a plant’s roots. Then there are symbiotic types, such as Azospirillium, which are associated with cereal crops and Rhizobium, which are associated with legumes. These latter examples physically attach and invade the root hairs, stimulating the growth of nodules, within which the bacteria can perform the conversion directly.

The caveat with these products is that there has to be nitrogen in the air to fix; they cannot make it from scratch.

So, if you have a closed-loop grow room with little to no outside air exchange, you might find the atmospheric levels too low for these additives to have a noticeable effect. The main gardens that will benefit are outdoor gardens, and indoor gardens vented with filtered air from outside.

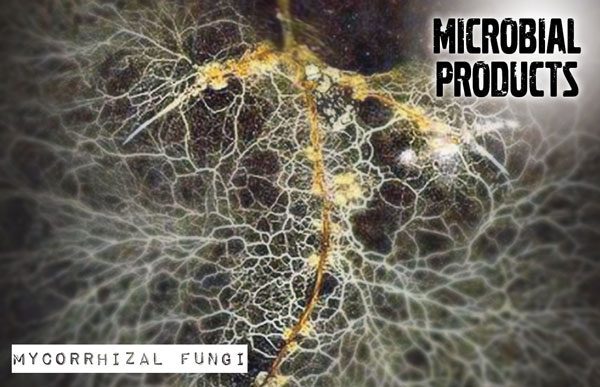

Mycorrhizal Fungi

This group has two main types, Endomycorrhizae (VAM), which are symbiotic and Ectomycorrhizae, which are non-symbiotic.

If you think of your plant’s roots as a net, a root system enhanced by mycorrhizae is many times larger, meaning more food is broken down for use by your garden.

When you see Rhizobacter, various species of Glomus, Rhizopogon, Pisolithus, and Scleroderma on a product, these are what you are using.

In the symbiotic kinds of Mycorrhizae, such as Glomus and Rhizobacter, there is a two-way flow of nutrients. These fungi attach to the roots and feed on exudates, which are simple carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis. In turn, the fungi mineralize nutrients and provide them to the plant. Ectomycorrhizae can only grow when attached to a living root system, but they can lay dormant as colonized root fragments or spores ready to populate new roots as they appear.

Ectomycorrhizae grow in and around roots, indirectly providing the plant with nutrition. These can propagate in the absence of a root system, having the ability to feed on soil carbon and nutrients; in fact, many common mushroom varieties are species of Ectomycorrhizae.

A potential issue in many systems is that these fungi are made dormant or outright killed off by too much phosphorous. It has been demonstrated in studies that as total P goes up, the growth and effectivity of these fungi goes down. So, if you are using these types of inoculants, it’s probably best to skip the applications of fertilizers with very high phosphorous levels, as one will cancel out the other.

Remember, even though you won’t be bombarding your plants with large amounts of P, the total amount made available to them by a more efficient root system will mean your garden still has ample supply.

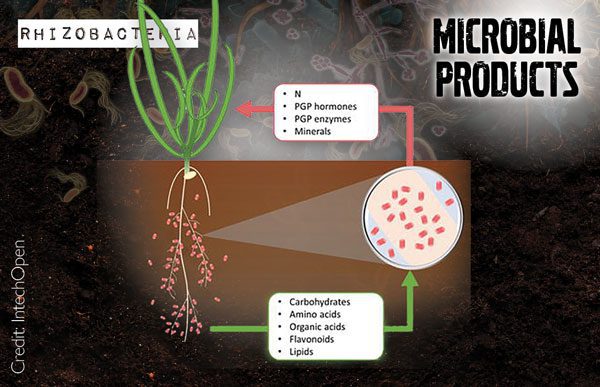

Rhizobacteria

In this group, there is a range of different types that are capable of performing many useful tasks.

Bacillus is the primary type utilized in many products and is usually provided in a variety of strains. Some of these are capable of performing nutrient solubilization of phosphorous (B.subtilis) and potassium (B.Megaterium); these are capable of making P and K, found in rocks and other very slowly available sources more available to the plant. Others, such as B.amyloliquefaciens and B.coagulans, provide potent root promoting and probiotic effects, being able to protect the plant and help them recover from pathogens like Pythium.

Other types (Beauvaria bassiana, Bacillus thurigiensis, Metarhyzium anisopliae, Lecanicillium lecanii) act as highly effective insect pathogens, while types such as Pochonia chlamydosporia and Anthrobotrys species are pathogenic to nematodes.

These bacteria quickly and efficiently populate the root system, so the best results are achieved when applied early in the crop cycle.

Trichoderma

Another example of symbiotic fungi commonly found alongside Mycorrhizae, and when used in the right proportions, it can have synergistic effects.

Trichoderma is some of the most prolific and easily found fungi in the natural environment. Have you have ever left moist coffee grounds to sit around too long and witnessed the white, then green growth? More likely than not, it was a kind of Trichoderma.

Because they grow rapidly and efficiently, they can control soil pathogens by successfully competing with them for space and nutrients; they are also powerful root growth promoters.

The rapid growth of Trichoderma can be a double-edged sword, though. If too much is applied, it can overwhelm other slower-growing beneficial species crowding them out. So, in general, stick to the minimum amount of applications necessary to see results.

Beneficial Anaerobic Bacteria

If you are familiar with the Japanese Bokashi composting system, then you have already used these.

It encompasses Lactobacillus (milk bacteria), Rhodopseudomonas (purple non-sulfur bacteria), Streptococcus, which are often the most common bacterial bloom found in soils, and Saccharomyces, which is a type of yeast.

These microbes thrive in low oxygen conditions and rapidly reproduce, readily digesting organic matter into nutrients the plant can assimilate. Because these microbes can thrive in situations that would typically be hosts to pathogenic bacteria, they create more healthy roots by filling these areas with plant-friendly microbes instead.

So, here’s the thing: there is only so much food and space, especially in containers, to provide nutrition to the plant and feed microbes. You can, to a certain extent, boost the amount of food available to them through the application of microbe foods like molasses and fish hydrolysate. However, if this is overdone, you can end up with a dominance of microbes that prefer the fast to digest food sources at the expense of ones that prefer organic matter. Ideally, we want to reduce inputs of fertilizers through the use of these additives, rather than having to add more to keep huge populations alive that are just existing to exist.

The way these products work is akin to growing mushrooms, where the media is inoculated either through drenching or preferably directly mixing the powder in before planting. You can also dust seeds and cuttings so that right from the start, the roots are populated.

Keep in mind is that Microbial inoculants aren’t like nutrients and additives that need to be applied with every single watering; they are living organisms capable of growing and reproducing. Once you have performed the inoculation, there is little to be gained by continually making more and more applications. So long as you are not killing these populations off with heavy applications of salt-based nutrients, high phosphorous levels, or chlorinated water, then they should continue to increase in the soil or grow media even after one application.

Like many things in growing, usually less is more, and this is a perfect example of that. The key to getting the best results is resisting the urge to go overboard. You might be working against your goals by using too many of these products too often. Not only will your gardens be better but you’ll save a few dollars too!

Keep it green and stay groovy.