This article originally appeared in Garden Culture Magazine UK30 & US28.

Ten years ago, at a local gardening group, I heard an elderly gardener extolling the importance of saving seeds with a great sense of urgency. At the time, I thought ‘why bother?’ when seeds are so cheaply available. However, the insights he provided that day changed my view and revealed a dark side to our food security. As a result, I started a seed saving group with bags of seed varieties from his garden, learned the skills to process and store seeds, and have spent the last decade as a dedicated seed saver.

Seed Heritage

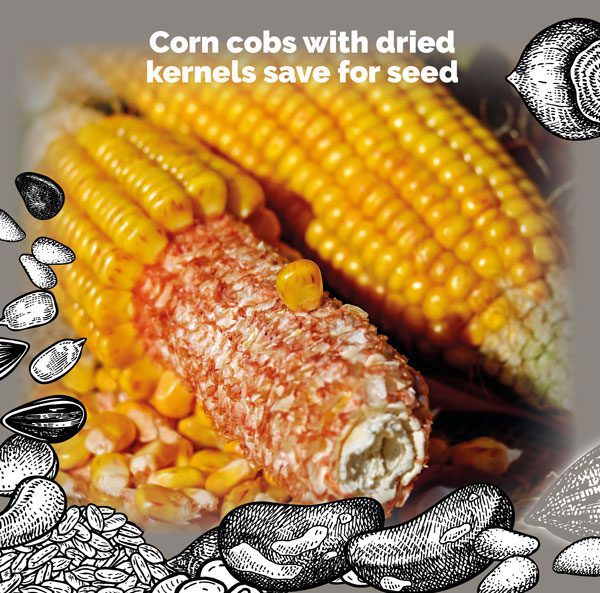

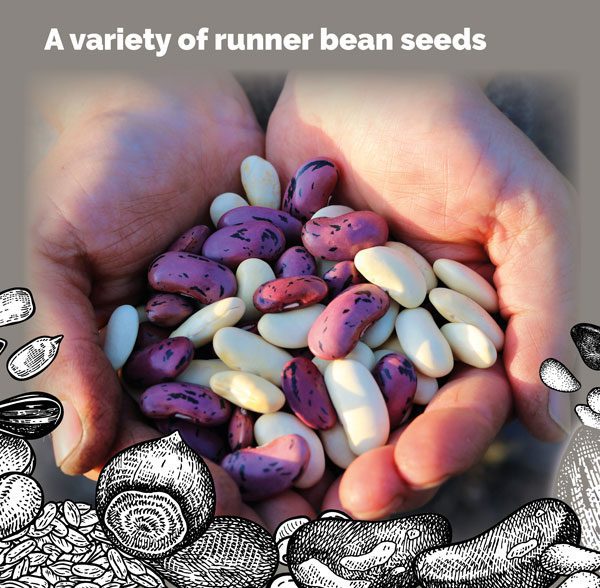

In the early part of this century, seeds were in the public domain. For generations, gardeners, farmers, and plant breeders have been seed ‘stewards’ taking personal responsibility for preserving a diverse range of food crops. Because seeds adapt to local conditions, climate, and soils, seed saving growers have been able to select the healthiest, most robust plants to collect seeds from. Farmers and plant breeders globally have saved their own varieties suited to particular conditions – just for their private gardens and farms.

This diverse heritage and careful selection meant small growers had access to unique cultivars, with many plants chosen because they were disease-resistant. Seeds were saved in backyards and on-farm from the crops with the best yields, flavor, color, shape, size, drought resistance, aroma, texture, resilience to pests, and many other beneficial characteristics.

Saving seeds has helped growers over generations save money by being self-sufficient and not having to buy more. Each year, their crops became better with careful selection, resulting in higher yields and fewer problems. Seed saving has always been an investment in future generations of plants. Rightly so, when seeds are the beginning and the end in the food chain.

Backyard gardeners and crop growers have also contributed to local seed banks around their countries. Without this input, small seed businesses could not survive, and our plant choices would be severely diminished. For many crops, only a small space is needed to collect enough seed on a commercial scale. Selling seeds is also a source of income.

Consolidation of the Seed Industry

However, since 1996, when genetically engineered (GE) seeds were introduced, continuous global mergers and consolidation of seed companies have dramatically transformed the commercial seed industry. In recent decades, a handful of agrochemical multinational companies have swallowed up small family-owned seed companies, minimizing competition and eroding the sustainable options for growers. Naturally, they can charge ever-increasing prices for seed.

By eliminating seed lines and limiting choices to hybrid seeds or genetically modified varieties that can’t be saved as they won’t grow true-to-type, these multinationals now control the vast majority of what farmers grow, and consumers eat. Farmers who buy these seeds are unable to save them for replanting. Currently, just four chemical companies largely control our future food supply, and that’s a worrying thought.

These global pharmaceutical/chemical giants have also used intellectual property laws to turn seeds into a commodity that now enables them to control the world seed supply. So rather than farmers freely creating new breeds of seeds for their benefit and public exchange, since the 1980s, there have been legal patents preventing such creativity and diversity. The threat of legal action discourages many farmers from replanting seeds they buy. These corporations have forcefully protected their IP rights, restricting the way seeds can be used, exchanged publicly, and saved for research.

The result is a weakening of our food security and the diversity of seeds in gardens, farms, and the marketplace. Plant genetic resources that should be in the public domain have been increasingly eliminated through escalating corporate control supported by court decisions.

Loss of Diversity

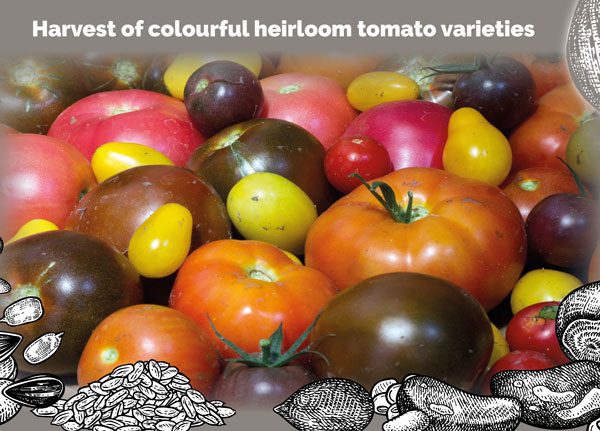

At the same time, the dramatic increase in monoculture crops to meet consumer and supermarket demands for perfect looking fruit and vegetables has led to other problems. There has been a drop in the diversity of crop varieties grown commercially, with a limited selection of seeds available to farmers.

Instead of growing a wide range of tomato varieties with the best flavor, aroma, and characteristics suited to the seasonal climate changes, the vast majority are bred for consistency of size, weight, skin thickness to avoid bruising in transport, farming equipment, and ease of picking at harvest time. Thousands of seasonally and locally adapted plant varieties have been lost. With this kind of monoculture farming, there’s often the need to use more herbicides and pesticides to grow the crop. Another financial and health cost to farmers, consumers, and the environment.

Organic farmers are particularly vulnerable to the reduction in seed availability and diversity. Organic growers depend on seeds bred for their capacity to resist pests and disease and the ability to outcompete weeds. The use of chemicals on conventionally grown crops suits the conglomerates who have both seed and farm chemical divisions. So they make money selling seeds farmers can’t grow on and the herbicide and pesticide products they need to sustain their crops.

There’s little incentive for biotech companies to research organic seed varieties when this eliminates the need for chemicals. Diverse heirloom seed varieties bred for many generations have been deleted in favor of investment into the most profitable seed lines. There’s no financial incentive for investment into seed cultivars that farmers can easily replant.

Diversity in the gene pool achieved by careful selection of seed varieties that survive through climate changes, resist pests or diseases, and that flower or fruit early or late, are sadly, significantly reduced. This lack of diversity reduces the buffer for growers. If one crop of a single cultivar fails, there’s a massive loss.

Unfortunately, a vast range of crops and plant varieties are now extinct. The increase in the development of genetically modified, hybrid, and sterile seeds based on terminator technology threatens the future of seeds, farmers, and food security.

Local and cultural knowledge that has been passed down through generations on preserving heirloom, wild and cultivated plant varieties has also largely vanished. Gardeners, farmers, and growers who could be self-reliant are predominantly outsourcing seeds rather than saving their own.

Nutrient-loss in food

Hybrid and genetically modified seeds grown for high yields and commercial convenience have tended to sacrifice nutrient value, flavor, and mineral content. According to SeedSavers.net, an Australian organization supporting seed saving, “The tradeoff between yield and nutrient level seems to be widespread across crops and regions, as plants partition their limited energy between different goals. Substantial data show that in corn, wheat and soybeans, the higher the yield, the lower the protein and oil content. The higher tomato yields (in terms of harvest weight), the lower the concentration of vitamin C, levels of lycopene (the key antioxidant that makes tomatoes red), and beta-carotene (a vitamin A precursor).”

Australian seeds

Ten years on, talking to my local nursery growers who have been selling vegetable, herb and flower seedlings for decades, staying viable is a struggle. It’s a very cost-driven business. The price of seeds has skyrocketed in recent years. Heirloom and non-GMO seed varieties have considerably diminished, replaced with hybrids that grow well for a single season. These growers can’t source enough bulk seeds within Australia, so rely on overseas hybrid seeds that won’t produce the same results in the next generation because they are genetically unstable. Seeds worth saving are those that grow true-to-type or the same as the parent plant. They preserve the unique traits from generation to generation. Growers are caught between a rock and a hard place.

Many small seed companies in Australia buy the bulk of their stock overseas. Imported seeds have to pass customs and quarantine restrictions. Quality standards for seeds in other countries can vary considerably to our own, so there’s always the concern about how safe they are.

Saving Life’s Building Blocks

With our climate throwing constant challenges at us to grow food, it’s never been more essential to have seeds that are resilient to change. We need to save and develop new varieties that do well in our local area. Here’s where an opportunity comes in.

The Open Source Seed Initiative

The Open Source Seed Initiative (OSSI), was inspired by the free and open-source software movement that provided alternatives to proprietary software. This organization was created by a group of plant breeders, farmers, seed companies, and sustainability advocates who want to ‘free the seed.’ Their goal is to make sure the genes in at least some seed are protected from use by intellectual property rights. For more information, visit osseeds.org.

In effect, this initiative creates a growing gene pool of ethically produced, fair trade seeds that can be used freely, without fear of the intellectual property being used by the corporate giants and removed from public use.

Seeds are Nature’s gift and a precious resource. As seed stewards, gardeners and growers can help preserve and pass these on to future generations. So, whether you choose to grow and save your seed, buy from a seed company that aligns with your values, or support a local seed saving group or seed bank, you can take steps to regain control of our seed supply actively. Every gardener and grower that takes action in this direction helps improve and sustain our seed diversity, and ultimately, our food security.

Carol Deppe, a retired geneticist, plant breeder, and author of Breed Your Own Vegetable Varieties, says “All gardeners and farmers should be plant breeders. Developing new vegetable varieties doesn’t require specialized education, a lot of land, or even a lot of time. It can be done on any scale. It’s enjoyable. It’s deeply rewarding.” More farmers and gardeners recognize they need to ‘take back their seeds.’ They need to save more of their own seed, grow and maintain the best traditional and regional varieties, and develop more of their own unique new varieties.

How does it work? OSSI helps maintain fair and open access to plant genetic resources worldwide. This ensures germplasm is available to farmers, gardeners, breeders, and communities of this and future generations. OSSI works with plant breeders who commit to making one or more of their varieties available exclusively under the OSSI Pledge: “You have the freedom to use these OSSI-Pledged seeds in any way you choose. In return, you pledge not to restrict others’ use of these seeds or their derivatives by patents or other means, and to include this Pledge with any transfer of these seeds or their derivatives.” This pledge is on all seed partner packaging.

Thank you for this vital information!

Glad you enjoyed the content!