I see a lot of sick plants. I have been professionally practicing cultivation and crop management for over 15 years. I have always loved gardening, which is probably one of the driving factors to why I got a degree in soil science. This year marks the ninth year that my crop management firm has been operating in the heart of the Emerald Triangle. My business journey has revealed a lot about the relationships that people have with their plants, and I have been bestowed with a firsthand peek into the practices, trends, and problems in the cannabis cultivation community.

Specializing in IPM

My business started at the beginning of 2012. It grew directly in response to the lack of access our cannabis cultivators had to science-based information about plants, soil, and the complexities of a growing system. Most of their information was coming through retail garden stores, internet forums, and product sales reps. Although there are knowledgeable folks in all these arenas, there is also a lot of incomplete, out-of-context, and wrong information.

There is no official standard or criteria applied to a “master cultivator” other than the grower’s perception of their plant prowess in underground culture. Adding to this disinformation is a sore lack of peer-reviewed work regarding cannabis. However, there are researched and robust methods from organic agriculture and crop science to readily apply to the knowledge gap in the cannabis cultivation sphere. This is how I ended up specializing in the diagnosis and Integrated Pest Management (IPM) for cannabis.

In my experience, I have observed that we tend to focus on pest eradication in agriculture, horticulture, and hobby gardening disproportionately. Maybe this is a reflection of modern culture, which tends to be mired reductionist thinking. Perhaps it is simply that we are evolutionarily rigged to depend heavily on our eyeballs to observe risks in our environment, and pests are much easier to detect than a virus or micro-fungi. In all likelihood, it is a blend of multiple elements. Perhaps this is a perfect example of how life more often exists in a This-AND-That paradigm rather than a This-OR-That paradigm, despite our brains’ achievements to reduce and dissect reality into consumable tolerable bits.

I would also argue that pests are usually not the inherent problem but a symptom of more significant issues a cultivator may not see or readily observe. A cultivator truly needs to develop and harness critical thinking to move beyond an acute pest issue and get to the core of their production problems.

Why Pests Take Over

Pests happen largely because the plant is stressed out. The plant communicates this susceptibility through its spectral signature or other chemical signals that instinctively draw in pests that have co-evolved to capitalize on plant vulnerability. Whether a weak phenotype causes this stress, disease, drought, overwatering, nutrient imbalance, or a lack of diversity – diversity in organisms AND farm practices – there is always an issue, aside from the pests, at the core of production problems. Killing the pest will not inherently solve that core problem, but when you have an acute pest infestation, managing that pest issue becomes a top priority, often neglecting the core issue.

Field Experience

Last year, a cultivator contacted me because of failing plant health. It was late July in Cali, so our Mediterranean climate leaves us dry and hot – a recipe for pest and disease susceptibility. This is when my phone rings off the hook, and my office becomes a revolving door of crop problems.

This cultivator had just transplanted their nursery stock and was growing a specific strain that had been problematic all season. I feel justified in saying this was a problematic strain because, at this time, 70-plus percent of our firm’s pest and disease samples were this one strain.

Unfortunately, these problematic strain health issues are usually seen in popular varieties fetching great market prices, so there is a genetic grab for these strains. Whether this grab results in a healthy phenotype often does not influence the growth of the cloner or the breeder. The cannabis culture has deep conditioning around its desire to find the “next best thing” – the next OG, gorilla glue, girl scout cookies, etc. This is in sharp contrast to almost all other plant breeding, which focuses heavily on disease and pest resistance. I point this difference out not to judge or condemn the cannabis industry but to highlight the weight of our cultural approach to growing our weed and consuming it. The cannabis culture heavily influences our cannabis products in a way that our standard modern agricultural crops are not.

Inspecting the Crop

So, back to my panicked client with that popular sickly strain they had procured from a licensed professional nursery. I went to the site immediately to scout their crop and screen for pests and diseases. The canopy of the transplants was drooping, wilted, yellowing, and failing to thrive. I carefully dug out a very sick specimen and shook off the dirt, revealing an inferior root color and development. All these signs were telling me a pathology was playing a role but was there more? As I did a lateral cut up the stem of this plant and laid it open, I saw a typical systemic fungal infection rotting the circulatory tissue inside the plant’s stem. This brown rot ran up the stem a few inches – pathology – check.

So, as I dissect this plant, I am asking about their cultivation practices. They reported preferring organic but minimal fertilizer inputs, they did not apply fertilizers based on soil testing data. Still, they spent lots of money on organic pesticides and did all kinds of preventative spraying. No biologicals. No pest/disease monitoring. No soil-building strategies.

But Wait, There’s More

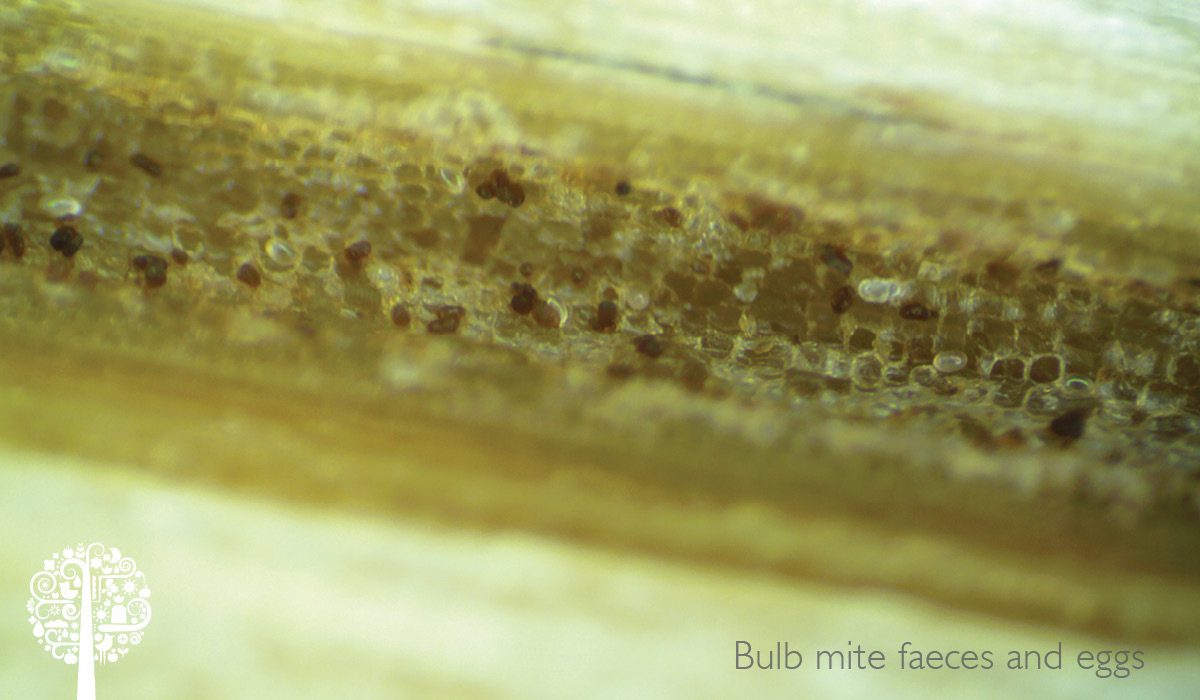

Next, I examined the stem under a low-powered 20-40-80 x dissection microscope. This is one of my favorite pest screening tools – magnified enough to spot most pests effectively but low enough to scan the entire leaf surface efficiently. I immediately saw an infestation of bulb mites up inside the stem of the plant.

Bulb mites are detritivores – meaning they eat dead organic matter. They are not sapsuckers like russet mites or aphids, and therefore, bulb mites aren’t really considered a huge agricultural pest risk unless they have taken over garlic or flower bulbs.

So essentially, I am looking at what isn’t a pest inside the very rotted stem of a cannabis plant. Since bulb mites are not sapsuckers, I felt safe to assume they were there for the buffet of rot that the pathology was producing as this disease infiltrated and killed off the roots and inner stem of this plant.

A Combination Effect

What we were witnessing was an exacerbated co-effect between two organisms. The more the bulb mites chewed at the roots eating the dead tissue, the more the disease was able to proliferate until the bulb mites could eat their way clear up into the stem of the plant.

So what caused this? Was it the Phenotype? Was it the bug? Was it the disease? All of these?

For me, this is where the word “wholistic” stops being some woo concept, blasé from rolling about in the zeitgeist and starts to be meaningful in real life. Every sick plant is a layered mystery to unravel, and every concerned grower asks identical questions when faced with a crop health issue. What is it? How do I fix it? I share this story because it fits a standard that most crop health issues fall within– it’s not just a bug that’s your problem, ever. Each case we solve is a unique result of personal belief, farm practices, genetics, and industry culture. In helping our clients unravel the web of personal paradigm, soil bio-diversity, strong genetics, and integrated farm practices, we have learned to go beyond providing just basics for plant life – food, water, light – and develop strategies for thriving.