When the coronavirus pandemic forced the world into lockdown last spring, a wave of anxiety came over Linda McDonald of Linlithgow, Scotland. Shortages associated with problems in the supply chain and panic buying made her want to take responsibility for producing at least some of her food. Jen Gates, also a resident of Linlithgow, needed something to take the edge off of quarantine. She decided growing produce was the healthiest way to do it.

“Just thinking about growing some salad was basically a gateway drug to getting more involved [with gardening],” Gates says. “Although my tomato anxiety ranks high on the scale, they’re probably [what] I’ve enjoyed getting to grow and ripen the most!”

The Edible Landscape Movement

McDonald and Gates aren’t alone. COVID-19 has sparked worldwide interest in the grow your own movement. People everywhere are beginning to understand that access to fresh, nutritious, and affordable foods cannot be taken for granted. Furthermore, experts consistently promote the mental health benefits associated with gardening. Sowing seeds and watching them grow helps people feel positive and take charge when everything else seems to be spiraling out of control. The parallels between human and environmental health have never been so clear.

The ladies are both members of an incredible campaign born in their town during the COVID-19 lockdown. Farmily is an initiative launched by Iain Withers, a Scottish farmer who wanted to boost the local food economy by helping his neighbors become more food secure and connect with what they eat.

Narrowboat Farm

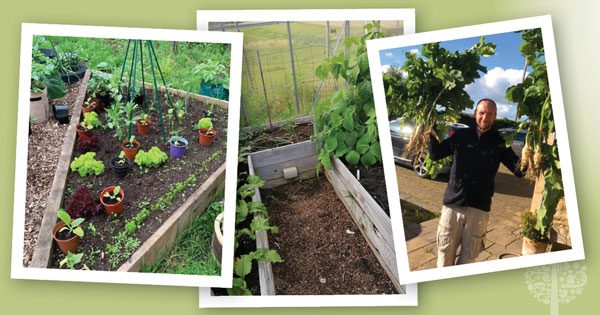

Withers and his team at Narrowboat Farm have helped distribute 500 starter packs to the community, which include things like pots and starter trays, compost, seeds, and planting instructions. They have also given 150 raised beds to people in the area. The response has been incredible, and to date, approximately 300 mini-farms have popped-up in yards all over Linlithgow. Withers says he can see many of his friends and neighbors are now hooked on growing, swapping seeds, produce, recipes, and advice.

“We know a lot of people will now see this as an annual project and not just a COVID-19 project,” he says. “We can tell by the expansions people are already planning and putting in place for their growing; installing polytunnels and greenhouses, building raised beds, and looking for advice for over-wintering veggies.”

Online Guidance

Beyond helping residents start gardens with tangible necessities, Withers has also created a Farmily Facebook group where people can come together virtually and share knowledge, stories of failures and successes, and ask various growing-related questions. The group is more than 600 members strong to date, and many expert gardeners participate and guide newbies through the various tasks, from seed to harvest. But Withers doesn’t care about one’s level of experience; he only requires that everyone in the group be respectful and support one another.

So far, so good. Sam McFarlane joined the group looking for advice on her quarantine gardening efforts and has made many friends along the way.

“I’m so glad I joined as everyone is so lovely and there’s no question too daft,” she explains. “It’s not often you find such warm communities online.”

Every member has their reasons for joining Farmily. Linda Hamilton needed advice after taking over the vegetable garden when her husband passed last year. Caitlin Sedge and Emily Oliver moved to the area during the lockdown and were looking for a way to integrate. Helen Wallace refers to Farmily as a lifeline that allowed her to interact with others at a time when she couldn’t leave her home. Shona and Colin Cavanagh wanted to introduce gardening to their children and help encourage them to eat more vegetables. Another member needed a source of food for her guinea pig, Calvin!

After hearing from many of the members, it is clear that Farmily has helped fill many voids and not just hungry bellies.

We Can All Do It

Farmily is proving that anyone can grow food for their families, even if they’re just starting out. Fiona Shields wanted to grow salad greens and potatoes with her two young boys while at home in isolation; after joining the group, she now has a couple of raised beds and a mini greenhouse on her property. The problem, she says, is making sure her harvest makes it the few steps to the kitchen.

“My boys keep asking to eat the peas straight from the pod in the garden,” she says. “Seeing the cucumbers grow has been amazing! I never thought I’d be able to grow so many edible things. I’ve never been able to keep a houseplant alive!”

From tomatoes, potatoes, cucumbers, and salad greens to beans, sweet corn, and more, there is an abundance of fresh, organic produce growing around Linlithgow now. Some harvests are big, and others are relatively small, but to Farmily, every single tomato counts.

Community Connections

Withers says he’s proud of the sense of community that has grown alongside the fruits and vegetables in his town. While Farmily is open to residents of Linlithgow, he says the concept can be applied in any community around the world.

“I think the Farmily model is a cracking model to follow,” he says. “It’s a friendly, supportive vibe using social media to connect people and experts. It includes very easy-to-follow guides for growing veg which break down the barriers for people to get into growing. Rather than being faced with way too much information on the internet, the group distills it down to personalized information and has the support network to help diagnose problems and suggest solutions when things get challenging.”

The group’s members can’t agree more, some of them viewing it as one of life’s most incredible experiences.

“The sense of community, achievement, and just the kindness of strangers will stay with me forever,” says Vikki Betty. “A much-needed light in the darkness.”